A new lab procedure that could allow fertility clinics to make sperm and eggs from people’s skin may lead to “embryo farming” on a massive scale and drive parents to have only “ideal” future children, researchers warn.

Legal and medical specialists in the US say that while the procedure – known as in vitro gametogenesis (IVG) – has only been demonstrated in mice so far, the field is progressing so fast that the dramatic impact it could have on society must be planned for now.

“We try not to take a position on these issues except to point out that before too long we may well be facing them, and we might do well to start the conversation now,” said Eli Adashi, professor of medical science at Brown University in Rhode Island.

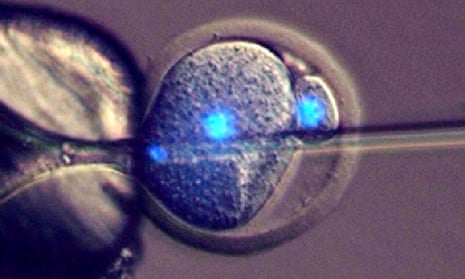

The creation of sperm and eggs from other tissues has become possible through a flurry of recent advances in which scientists have learned first to reprogram adult cells into a younger, more versatile state, and then to grow them into functioning sex cells. In October, scientists in Japan announced for the first time the birth of baby mice from eggs made with their parent’s skin.

The technology is still in its infancy and illegal to attempt in humans in the UK and the US. But, writing in the journal Science Translational Medicine, Adashi, along with Glenn Cohen, a professor of law at Harvard Law School, and George Daley, dean of Harvard Medical School, argue that it may be possible to make human eggs and sperm from skin “in the not too distant future”.

IVG could offer fresh hope for infertile people, including those who are unable to have children after cancer treatment. Because chemotherapy can destroy reproductive cells, patients sometimes store their sperm or ovarian tissue to use once they have recovered. With IVG, it may be possible to collect skin cells from a patient and turn them into healthy sperm or eggs for use in IVF later on. The procedure could transform IVF in other ways too, the researchers say, by making egg donors obsolete and replacing the standard hormonal stimulation that is used to make women produce eggs.

But alongside its potential benefits, IVG throws up a host of situations that pose fresh legal and ethical questions. If the procedure ever became simple and inexpensive, clinics could manufacture almost limitless supplies of sperm, eggs and embryos. “IVG might raise the specter of ‘embryo farming’ on a scale currently unimagined, which might exacerbate concerns about the devaluation of human life,” the researchers write.

For a couple having fertility treatment, IVG could mean that instead of doctors choosing the best from half a dozen or so embryos, they could select from a pool of hundreds. And while that may be a benefit, it could intensify “concerns about parents selecting for their ‘ideal’ future child”, the authors write.

Cohen said he and his colleagues were not expressing their personal views on how IVG might be used. Instead, they wanted to start a debate about the potential ramifications of using the procedure in humans. Offering up one example, Cohen said: “For those who oppose embryo destruction, creating, say 100 embryos when you are only going to use five for implantation may seem problematic.”

What were previously no more than science fiction scenarios may become more realistic with IVG, the researchers suggest. In one extreme example described by Cohen, skin cells might be collected from Brad Pitt’s hotel bathtub and used to make sperm for insemination. “Should the law criminalise such an action? If it takes place, should the law consider the source of the skin cells to be a legal parent to the child, or should it distinguish between an individual’s genetic and legal parentage?” the researchers ask in the article.

In another hypothetical situation, IVG could be used to make sperm and eggs from more than two people. These could then be combined to make children with three or more genetic parents. The case raises serious questions about the rights and responsibilities of each contributing parent, the authors write.

It will take many more studies, including experiments in monkeys and other animals, before scientists know whether IVG is effective and safe enough to attempt in people. The first steps in humans will be to make sperm from a man’s skin cells and eggs from a woman’s skin. In principle, it would be possible to make sperm from a woman’s skin cells, and use them to fertilise her own eggs.

“When new technologies come out, the law is often accused of playing catch-up,” Cohen said. “Far better to think and discuss on the front end, even if some of this never comes to pass, than scramble on the back end to gap-fill, in my humble opinion.”

“With science and medicine hurtling forward at breakneck speed, the rapid transformation of reproductive and regenerative medicine may surprise us,” the authors conclude. “Before the inevitable, society will be well advised to strike and maintain a vigorous public conversation on the ethical challenges of IVG.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion